October 7, 2020

Economics + Asset Value

Summary

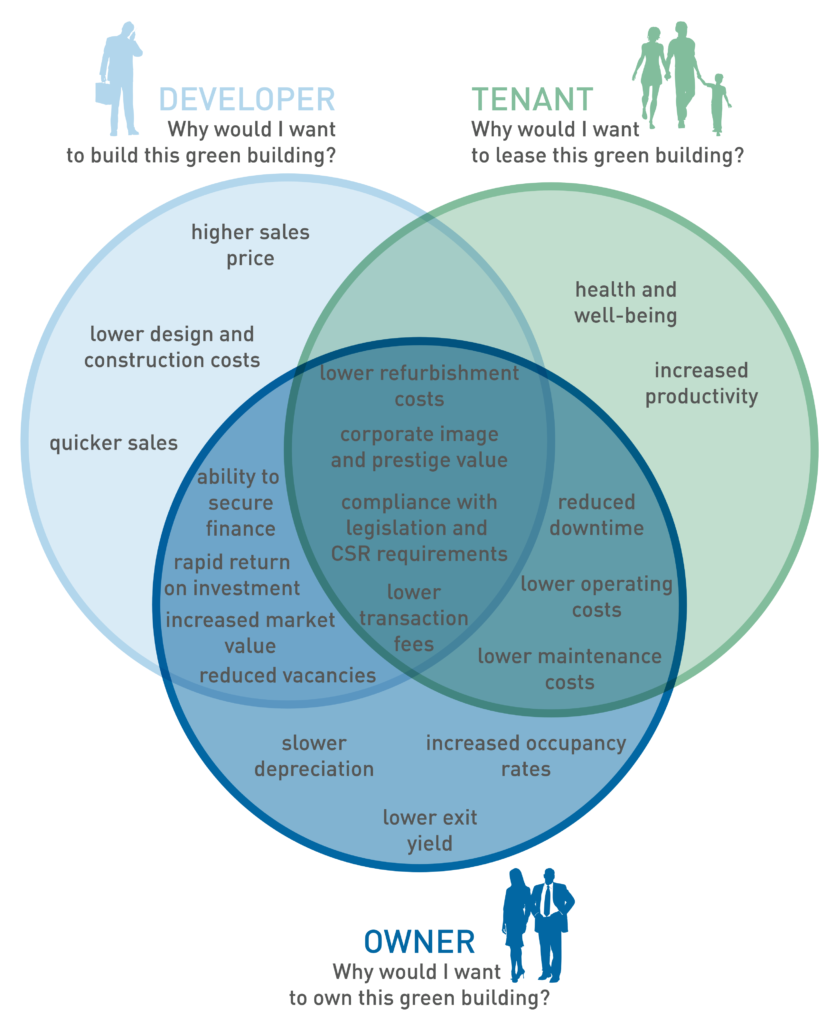

Asset value is commonly perceived as market value, meaning what a property would sell for based on the local real-estate market and specific features of the property. The perception of asset value, however, can vary for the various stakeholders of a building or project (WGBC 2013). Many developers who plan to immediately sell a property are interested in the short-term value of their property and attracting potential occupants or sales. Conversely, long-term building owners are motivated by increased occupancy rates, and longer term indications of market valuation. Tenants look for buildings that might increase productivity or health and wellbeing of their workforce and potential for lower operating or maintenance costs when looking to lease new space. How a building responds to these motivations impacts the asset value of a property. For example, green buildings have been found to have a positive influence on asset value (WGBC 2013). Two of the main elements that contribute to the value of green buildings include lower operating expenses and an enhanced image associated to green certifications which can attract higher quality tenants and improve retention. Both can lead to higher occupancy rates, higher rental/lease rates, and lower capitalization rates which lead to higher transaction prices (WGBC 2013).

Figure 1 from a report by the World Green Building Council in 2013 illustrates elements of green buildings as perceived to the various stakeholders of a building (WGBC 2013).

Overview

I. Green Labeling

The most common green building certifications in the US such as Energy Star and LEED are associated to higher market rates and are able to achieve higher rents than non-labeled buildings (Eichholtz 2010). Green buildings can have an economic advantage because they are likely to have “longer economic lives, lower marketability risk, and a lower risk of technical and regulatory obsolescence” (Reichardt 2012). Green buildings can signal a social and environmental awareness and can help achieve a favorable reputation for the owners and occupants (Eichholtz 2010).

Economic Implications

Green labeled buildings have been found to be more desirable and marketable and can achieve higher rental rates than conventional buildings (Bartlett 2000). For developers, environmentally friendly labels can help sell a building quickly for a higher price. Owners and occupiers are interested in the favorable image that is conveyed by being associated with green buildings that have lower environmental impact as well as achieving energy efficiency (Bartlett 2000). Interest in occupying green certified buildings has been shown to contribute to a higher market value for the property and the ability to charge rental premiums (Reichardt 2012). In a study by Eichholtz, buildings with a green rating achieved higher rental rates at approximately three percent higher per square foot than similar nonrated buildings (Eichholtz 2010). A study done by Fuerst confirms that rental premiums can be charged for green certified buildings. They found that LEED certified buildings could charge up to a five percent premium and Energy Star up to a four percent rental premium (Fuerst 2011). A study by Reichardt also endorses that higher rental premiums can be charged for LEED and Energy Star labeled buildings (Reichardt 2012). The level of certification can impact the potential increase in rent. LEED certification has several levels from Certified to Platinum. A report by the World Green Building Council highlights that there is “an average three percent increase in rent for each increase in certification level” (WGBC 2013).

Sales prices were also found to be higher in green certified buildings. The study by Eichholtz found sales prices of green buildings to be up to 16 percent higher than a similar conventional building (Eichholtz 2010). Fuerst found a 25 percent price increase for LEED certified buildings and 26 percent for Energy Star certified buildings (Fuerst 2011). A report by Kaplow highlights an increase in market value with LEED buildings selling at $171 USD ($196 in 2020 dollars) more per square foot and Energy Star selling for $61 USD ($69 in 2020 dollars) more per square foot more than non-certified buildings (Kaplow 2011).

In addition, occupancy rates tend to be higher in green certified buildings. Reichardt found that Energy Star label buildings had a 4.5 percent increase in occupancy rates (Reichardt 2012). The report by Kaplow stated that LEED buildings have a 4.1 percent higher occupancy rate and Energy Star buildings have a 3.6 percent higher occupancy than non-certified buildings (Kaplow 2011). In a case study of a green retrofit of a 1980s office building in UK found that by implementing a green retrofit, they were able to add value to the asset and secure building tenants. Before the retrofit, the real estate fund manager was looking for new tenants. Skanska, who was an existing tenant whose lease was up found that the building did everything their company needed except comply with company’s green aspirations. By implementing the green retrofit, they were able to secure Skanska as a tenant and sign a new ten year lease, “immediately adding value to the asset” (WGBC 2013).

II. Operational Cost Reduction

Operational expenses are the out-of-pocket costs for maintaining and running a space (Katz 2020). The type of expenses vary between different building typologies and ultimate responsibility for these expenses can fall on individual owners, HOAs, lease-holders, or landlords depending on ownership structure and contractual agreements. According to BOMA, typical operational costs for a private sector office building include cleaning, utilities, fixed costs, parking, road and grounds, repair and maintenance, and real estate taxes (BOMA website). For a typical company, operational costs account for 6% to 15% of total business expenses (Attema 2018).

High performance design has the potential to significantly reduce operational cost. For more information on pathways to reduce operational cost see Value Case 2. The following section outlines how reducing operational cost effects asset value.

Economic Implications

Reductions in operational and maintenance related cost are one of the primary factors used to justify the implementation of green buildings. Efficiencies in water and energy can have significant cost benefits. In a case study of a mixed-use development in Cape Town , South Africa by implementing energy saving systems, the development experienced a 17% drop in energy costs and estimate savings of $640,000 USD per year. Water conservation and waste management strategies were also implemented in the project, and have resulted in annual savings of $162,000 USD. Due to the energy and cost savings, the project has received a lot of recognition which has added to the image of the development. This has added attraction to the development and increased the marketability to future tenants (WGBC 2013). Operational cost reductions have been found to be a large factor in how owners of green buildings can charge rental premiums and increase the market value of the project (WGBC 2013). The difficulty of using operational cost reduction as an added asset value is that those making the decisions from the start are often not the ones who pay the operating costs for the building. Investors and developers pay the initial costs, but since they will not hold the asset for very long, long-term cost evaluation is not necessarily a priority. However, if they are able to use the reduction in operational costs as a marketing strategy to help charge a premium for rentals or asset sales price, investing in the implementation of energy and water saving systems could be more attractive (Bartlett 2000).

A study by Eichholtz on green real estate found that on average, every dollar saved in energy cost increased the market value by 18.32 dollars assuming a cap rate of 5.5 percent. If that cap rate were raised to 6 percent, a 20.73 dollar increase in market value was found per dollar of energy savings (Eichholtz 2010). Another study by Wiley indicates that Energy Star and LEED labeled properties can achieve premium rents attributing some of this value to the tenant’s savings in operating expenses (Wiley 2010). It was also highlighted in a report by the World Green Building Council that by reducing operational costs, green buildings can charge rental premiums and have an increased market value (WGBC 2013). Green buildings can also be simpler to operate due to their passive nature, increasing the attraction to the owner-occupier. This simplicity makes the whole life cost much lower than a normal building and less maintenance and attention needs to go into running the building which contributes to improved occupancy rates (Bartlett 2000, Wiley 2010).

III. References

Review Articles

- Attema, Jeremy, Fowell, S.J., Macko, M.J., & Neilson, W.C. “The Financial Case for High Performance Buildings.” San Francisco: Stok LLC. (2018).

- Bartlett, Ed. “Informing the decision makers on the cost and value of green building.” Building Research & Information 28, no. 5-6 (2000): 315-324.

- Kaplow, Stuart D. “Does a green building need a green lease.” U. Balt. L. Rev. 38 (2008): 375.

- Wiley, Jonathan A. “Green design and the market for commercial office space.” The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 41, no. 2 (2010): 228-243.

Primary Research

- Eichholtz, Piet, Nils Kok, and John M. Quigley. “Doing well by doing good? Green office buildings.” American Economic Review 100, no. 5 (2010): 2492-2509.

- Fuerst, Franz, and Patrick McAllister. “An investigation of the effect of eco-labeling on office occupancy rates.” Journal of Sustainable Real Estate 1, no. 1 (2009): 49-64.

- Fuerst, Franz, and Patrick McAllister. “Green noise or green value? Measuring the effects of environmental certification on office values.” Real estate economics 39, no. 1 (2011): 45-69.

- Reichardt, Alexander, Franz Fuerst, Nico Rottke, and Joachim Zietz. “Sustainable building certification and the rent premium: a panel data approach.” Journal of Real Estate Research 34, no. 1 (2012): 99-126.